The small, tired eyes stared into his coldly. “I have never seen England.” The eyes wandered away round the table. ” When I was last in Rome”, he said, ” I saw a magnificent parade of the Italian army with guns and armoured cars and aeroplanes.” He swallowed his raisins. ” The aeroplanes were a great sight and made one think of God… They made one think of God. That is all I know. You feel it in the stomach. A thunderstorm makes one think of God, too. But these aeroplanes were better than a storm. They shook the air like paper.”

Watching the full self-conscious lips enunciating these absurdities, Graham wondered if an English jury, trying the man for murder, would find him insane. Probably not: he killed for money; and the Law did not think that a man who killed for money was insane. And yet he was insane. His was the insanity of the sub-conscious mind running naked, of the ” throw back”, of the mind which could discover the majesty of God in thunder and lightning, the roar of bombing planes, or the firing of a five-hundred-pound shell; the awe-inspired insanity of the primaeval swamp. Killing, for this man, could be a business. Once, no doubt, he had been surprised that people should be prepared to pay so handsomely for the doing of something they could do so easily for themselves. But, of course, he would have ended by concluding, with other successful business men, that he was cleverer than his fellows. His mental approach to the business of killing would be that of the lavatory attendant to the business of attending to his lavatories or of the stockbroker towards the business of taking his commission: purely practical.

– Eric Ambler, Journey into Fear (Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., London, 1940)

Category: Lobby

Noir Poets: Abraham Polonsky

I had forgotten Doris for a moment,

And then I was glad she was there, waiting.

She was someone to talk to.

We walked down Wall Street to trinity church,

And she kept watching me,

Wondering what had happened there in that office of mine.

I think she had made up her mind

To fall in love with me.

And I wouldn’t have minded at another time.

It would have been a change from the kind of women I knew.

She wanted me to talk to tell her, to convince her

That I didn’t realize what I was doing,

That I didn’t understand the business I was in,

But I enjoyed the idea of convincing her that I did.

When was it, Mr. Morse, that Tucker walked in?

I’ll tell you.

I’ll tell you, Doris,

how the boom was on,

And I could feel money

Spread all over the city

like air,

Like perfume from those

flowers I gave you.

the smell of money.

And was that when Tucker walked in?

Yes. And I’m a man.

What have I got to do

with Tucker?

But he opened his pocket,

and I jumped in headfirst.

I sat there

and measured my strength.

I had so much, Doris-

That’s the way I figured-

So much strength,

And it all worked out

this way.

I didn’t have enough strength

to resist corruption,

But I was strong enough

to fight for a piece of it.

And now you want to get out. Is that what your trouble is?

My trouble is, Miss Lowry,

that I feel like midnight,

And I don’t know

what the morning will be,

Except, for a little while,

I felt pretty easy here,

Talking to you,

liking you.

You’re the only one

I ever talk to, Doris.

You’re the only one

I ever talk to,

And I don’t know why,

Except that

you caught me tonight

When I would have talked

to the devil.

But I… thank you.

It’s the truth, Doris.

A man doesn’t tell lies

at midnight,

But now I talk to you

because you’re Doris.

You see how lovely

that makes you?

What are you now?

Someone to say,

To fool himself

or me, that…

that you love me?

Not so soon.

I won’t tell you that,

But it would be such

a comfort to me

To kiss you.

Is that strange?

No. No, that isn’t strange.

The Force of Evil (1948)

Direction and Screenplay by Abraham Polonsky. Based on Ira Wolfert’s novel Tucker’s People.

Tension (1950): A house in the suburbs? “Are you kidding?”

A reversal of sex roles so potent it has to rank as one of the best expositions in noir of the femme-noir as ball-breaker…

A neat little noir from director John Berry, who also had a hand in the script by Allen Rivkin, which was adapted from a story by John Klorer. Cheap blonde Claire (Audrey Totter) leaves meek and earnest hubby Warren (Richard Basehart) for a Malibu-type with dough. The boyfriend ends up on ice, with hubby framed for the murder. Sardonic hulk and investigating cop Lt. Bonnabel (Barry Sullivan) plays with Claire to fish out the killer. There is nice support from William Conrad as Sullivan’s buddy, and Cyd Charisse as a very good girl.

You just have to relish Totter – she is the devil in no disguise. In an early scene Claire is having a piece of strawberry pie with cream at the counter of a drug store and is eyeing an advert for a mink in a magazine – hubby the night druggist at the other end of the store is slaving over mortar & pestle to keep her in a style of life she doesn’t desire – when she is picked up. Even a b-girl would have held out a bit – the exchange is pure sleaze:

Stunning, isn’t it?

On her.

It’d look better on you.

Think so, huh?

Yeah.

Thanks, that’s nice.

And I got something nice to talk about.

So?

Yeah. Wanna hear more?

Where you parked?

Around the corner. Gray sedan.

In Silver & Ward’s ‘Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference’ (1992), Claire is described as a “classic femme fatale, a woman who drives men to the brink of disaster merely on a whim”. I dispute the contention that Claire is a femme-fatale. Sure she is mean and manipulative, and uses sex to get what she wants – “Hey, what’s better than money?” – but she does not use men as surrogates. She is quite capable of doing whatever needs to be done to achieve her sordid ends on her own. This said, there is a simply brilliant scene the next morning after Claire’s escapade with the gray sedan, that portrays a reversal of sex roles so potent it has to rank as one of the best expositions in noir of the femme-noir as ball-breaker.

Hubby returns to their apartment in the morning after ending his night shift. Anxiously hoping against hope he finds Claire asleep in the marital bed – and is fooled into thinking she has spent an innocent night at home. His mood lifts and he makes her breakfast – the toast is burnt – and tells her he has a surprise. The next scene cuts to the couple in their car – Warren is driving – as it pulls up to a new bungalow in a raw housing estate [my reconstruction]:

Claire (annoyed): What are you stopping here for?

Warren (happily opening the car door): Look. Isn’t that a beauty?

Claire (combing her hair and staring into the mirror of her compact): Are you kidding?

Warren (abashed but still in good humor): Gee, it would be wonderful to live out here, darling. Fresh air, room to entertain. It’s great for kids.

Claire (petulant): You wanna know something? I think it’s a miserable spot. It’s 30 minutes from nowhere.

Warren (exasperated): I thought this was what you wanted. What do you think I took the night shift for? Saving and doing without so we’d have enough money to do this.

Claire: We still don’t have enough.

Warren: The FHA even approved the loan.

Claire: Fine. Let them live here.

Warren gets out of the car and walks toward the house singing its praises… “Darling, at least look at it”. Meanwhile Claire shifts into the driver’s seat, she is wearing a plain dark top and flannel pants. She starts sounding the car horn loudly, closes the driver’s door, and starts the engine: “You comin?”.

Warren turns back mortified, while Claire revs the engine like a young punk, the exhaust fumes confronting Warren as he walks behind the car before getting into the passenger’s seat.

At the Speed of Noir: Dames in Cars

James Gunn’s ‘Deadlier than the Male’: Psychology of the Femme-Fatale

Helen Brent had the best-looking legs at the inquest. She had a white sharkskin suit that had cost $145. She had an air of impeccable good breeding that had cost a great deal more. From the looks of things, she was no usual divorcee. Obviously, she was a woman of great wealth, of travel, of culture, of charm; she was a gorgeous blonde; she had been around. Perfectly poised, she crossed her legs with stunning and careless showmanship.

Her name was Helen Brent, she said, and she was thirty-one; her home was in San Francisco; she was in Reno to get a divorce from her husband, Mr. Charles Brent.

She had been in Reno—how long?

Six weeks; during that time she had stayed at a boarding house on the edge of town, run by a Mrs. Krantz and her daughter, Miss Rachel Krantz; Miss Rachel Krantz was in the courtroom.

On the previous Thursday, she had left the Krantzes’ and gone to the Hotel Riverside?

Yes.

She had gone back to the Krantzes’ at eleven that night to pick up a handbag?

Yes.

And about what time had she left the Krantzes’ to go to the hotel?

About five.

Deadlier than the Male is the only novel by American writer James Gunn, who wrote the book in 1943 at the age of 23. The story was adapted by Hollywood for the 1947 film noir Born to Kill. In his short life – he died at the age of 46 in 1966 – Gunn wrote screenplays for movies and television. Little is known of his life, and he remains a tantalizing mystery.

The novel was chosen as the 50th book to be published by French publisher Gallimard under the Le Série Noire imprint. In 1966, the radical French philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, in a tribute on the publishing of the 1,000th title in the series, which was started in 1945 by editor Marcel Duhamel, wrote:

The most beautiful works of La Série Noire are those in which the real finds its proper parody, such that in its turn the parody shows us directions in the real which we would not have found otherwise. These are some of the great works of parody, though in different modes: Chase’s Miss Shumway Waves a Wand; Williams’s The Diamond Bikini; or Hime’s negro novels, which always have extraordinary moments. Parody is a category that goes beyond real and imaginary. And let’s not forget #50: James Gunn’s Deadlier than the Male.

The trend in those days was American: it was said that certain novelists were writing under American pseudonyms. Deadlier than the Male is a marvelous work: the power of falsehood at its height, an old woman pursuing an assassin by smell, a murder attempt in the dunes—what a parody, you would have to read it—or reread it—to believe it. Who is James Gunn anyway? Only a single work in La Série Noire appeared under his name. So now that La Série Noire is celebrating the release of #1000, and is re-releasing many older works, and as a tribute to Marcel Duhamel, I humbly request the re-release of my personal favorite: #50.[1]

In a review in 2008 of the re-issue by Black Mask Publishing, British academic Robin Durie said of the novel:

It’s very hard to imagine the almost hallucinatory events of the novel translating to the big screen in 1947 [in Born to Kill] – although it’s just about possible to imagine John Waters or David Lynch making some headway with it. It’s also possible that Claude Chabrol might have fancied having a go at turning it into a movie, based on his admiration for the book: “It has a freely developed plot and an absolutely extraordinary tone, pushing each scene towards a violent, ironic and macabre paroxysm…an unexpected dimension, a poetic depth… Of course, nothing like this has ever been written before. The parody is wildly inconsistent, but Deleuze is surely right when he says that, by this means, Gunn creates directions in the real which are wholly new.” … At the same time, Chabrol is correct in his capturing of the intensity of the rhythm of Gunn’s writing. Each chapter builds – or perhaps better, meanders – towards, or into, extraordinary points of what are, in effect, bifurcations. It is as if the novel is following those bifurcating pathways described by Borges.”[2]

Deadlier than the Male is like no other noir fiction. The weird story of a deranged con-artist who marries into a wealthy San Francisco family, while told in the third person, reveals the thoughts and motivations of the central character, an attractive 30-something divorcee, Helen Brent. In film noir-style, the book opens in flash-back as Helen gives testimony at an inquest in Reno into a double murder. Helen, in Reno to engineer a quick divorce, by chance stumbles on the victims of a double domestic murder. We know the killer and that, unbeknown to Helen, he was still at the murder scene when she came across the bodies. Gunn’s story goes on to explore how the lives of these two people become entwined, and how lies upon lies lead to the final denouement where Helen’s true self is revealed to not only the reader but to herself. As the story plays out there is a virtual cavalcade of odd-ball characters drawn with keen psychological insight in a series of ongoing scenarios that are woven in an almost surreal “more or less undifferentiated present” [Durie].

These psychological insights are strongest as we follow Helen’s obsession to find out the ’truth’. A truth which as she uncovers seeks to hide by lies and intimidation. Her motivations are never fully fathomed but at the end we know fully what she is capable of. Helen is sexy, smart, charming, even loving, and constantly battling her better instincts to strive for a physical security which can only be bought by money – and lots of it. Pitted against her is a lurid drunken widow out to find the killer out of loyalty to one of the victims – her debauched friend and drinking companion who dallied with younger men. The comic encounters of this ridiculous aging sleuth are nevertheless successful – albeit not without real danger – she just escapes death at the hands of psychopathic hood in the sands dunes of Frisco in a scene as violent and perverse as you would find in a Coen Bros. movie.

… ‘The truth is, Helen, you’re uncivilized still. You’re out of the jungle, or to be more exact, you’ve gone back to it. You have enough intelligence and enough courage to realize you don’t need other people. You’ve decided to live alone with your strength. And that’s where you fall down’…

…Helen’s mind seemed to grow endlessly inside her head. She saw herself standing alone, in an infinity of space and matter. She was quite solitary, and very strong. No one was close to her, no people. She would never be able to have anyone close to her again.

A must read. Get the re-issued paperback here – also available is the eBook version for 99cents.

Postscript: The obscure French film Corps et biens (1986) from director Benoît Jacquot is also based on Gunn’s novel.

[1] Gilles Deleuze, The Philosophy of Crime Novels

[2] Book review by Robin Durie

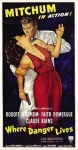

Great Noir Posters: Erotic licence

The Green Cockatoo (UK 1937 65min): The Seeds of British Noir

Graham Greene, who wrote the source novel and worked on the screenplay of perhaps the greatest British noir, Brighton Rock (1947), scripted the British hard-boiled crime thriller The Green Cockatoo (aka ‘Four Dark Hours’ or ‘Race Gang’). After the movie was screened at the 43rd New York Film Festival in September 2005, Keith Uhlich of Slant, wrote: “Director William Cameron Menzies, an award-winning production designer, grounds The Green Cockatoo in expressionist shadows that anticipate Carol Reed’s The Third Man (the ne plus ultra of Greene’s cinema output) and the writer himself is evident via the piece’s sense of a veiled, yet inescapable moral outcome with which each character must deal.” Hal Erickson in the All Movie Guide says of the film: “Filmed in 1937, the British Four Dark Hours wasn’t generally released until 1940, and then only after several minutes’ running time had been shaved off. The existing 65-minute version stars John Mills, uncharacteristically cast as a Soho song and dance man. When Mills’ racketeer brother Robert Newton is murdered, Mills takes it upon himself to track down and punish the killers. Rene Ray, the girl who was with Newton when he died, helps Mills in his vengeful task”. Bosley Crowther in the NY Times in 1947: “With all its disintegration, though, [The Green Cockatoo] is still better melodramatic fare than is usually dished out to the patient Rialto audiences… An unknown here, Rene Ray, is very attractive as a wide-eyed country girl unwittingly involved in the Soho proceedings”. Film writer for The Guardian, Andrew Pulver, wrote in 2008 that the movie “has a similar [to film noir] commitment to the boiled-down essentials of the crime genre”. Max Green, who later lensed Night and the City (1950) for Jules Dassin, is DP and the film’s score was one of the first from Miklós Rózsa.

Graham Greene, who wrote the source novel and worked on the screenplay of perhaps the greatest British noir, Brighton Rock (1947), scripted the British hard-boiled crime thriller The Green Cockatoo (aka ‘Four Dark Hours’ or ‘Race Gang’). After the movie was screened at the 43rd New York Film Festival in September 2005, Keith Uhlich of Slant, wrote: “Director William Cameron Menzies, an award-winning production designer, grounds The Green Cockatoo in expressionist shadows that anticipate Carol Reed’s The Third Man (the ne plus ultra of Greene’s cinema output) and the writer himself is evident via the piece’s sense of a veiled, yet inescapable moral outcome with which each character must deal.” Hal Erickson in the All Movie Guide says of the film: “Filmed in 1937, the British Four Dark Hours wasn’t generally released until 1940, and then only after several minutes’ running time had been shaved off. The existing 65-minute version stars John Mills, uncharacteristically cast as a Soho song and dance man. When Mills’ racketeer brother Robert Newton is murdered, Mills takes it upon himself to track down and punish the killers. Rene Ray, the girl who was with Newton when he died, helps Mills in his vengeful task”. Bosley Crowther in the NY Times in 1947: “With all its disintegration, though, [The Green Cockatoo] is still better melodramatic fare than is usually dished out to the patient Rialto audiences… An unknown here, Rene Ray, is very attractive as a wide-eyed country girl unwittingly involved in the Soho proceedings”. Film writer for The Guardian, Andrew Pulver, wrote in 2008 that the movie “has a similar [to film noir] commitment to the boiled-down essentials of the crime genre”. Max Green, who later lensed Night and the City (1950) for Jules Dassin, is DP and the film’s score was one of the first from Miklós Rózsa.

I found The Green Cockatoo an entertaining ‘curio’ (to paraphrase Pulver). While there are elements that point to noir, the picture is more a melodramatic thriller. A Soho seediness to the affair is enhanced by the very cheapness of the production. Most of the action plays out during a London night after a young provincial ingenue arrives on a midnight train from the sticks and has a chance encounter. The darkened sets have a definite moodiness. A night scene introducing the Soho night-club, ‘The Green Cockatoo’, around which the action pivots, has an accomplished mis-en-scene. We see a couple stroll past a copper on the beat who walks up to a b-girl holding up a lamp-post in front of the club – the bobby stares the girl down and she moves on.

There is a lot of action packed into just over an hour, but the plot relies on a touch too many contrivances and misunderstandings. There is a nice chemistry between Mills and Ray, who is quite beguiling, with some nice patter and cute innuendo. A number of scenes are played for laughs, which adds a pastiche quality. Indeed, scenes at a plush hideout with a butler, played beautifully by Frank Atkinson, are laugh-out-loud funny. This said, the pastiche factor detracts overall, and it is jarring to hear English characters using very unlikely expressions such as ‘guys’ and ‘dames’. Though the Hollywood influence is obvious, there are no guns, only flick-knives.

Max Green’s lensing is most deserving of praise, and these shots from the picture attest to its expressionist elements:

An interesting historical artifact, and worth seeking out. Not on DVD.

Noir Poets: Henry Miller

Crime begins with God. It will end with man, when he finds God again. Crime is everywhere, in all the fibres and roots of our being. Every minute of the day adds fresh crimes to the calendar, both those which are detected and punished, and those which are not. The criminal hunts down the criminal. The judge condemns the judger. The innocent torture the innocent… Can you hold the mirror to iniquity when it is close at hand? Have you looked into the labyrinth of your own despicable heart? Have you sometimes envied the thug for his forthrightness? The study of crime begins with the knowledge of oneself. All that you despise, all that you loathe, all that you reject, all that you condemn and seek to convert by punishment springs from you. The source of it is God whom you place outside, above and beyond. Crime is identification, first with God, then with your own image. Crime is all that lies outside the pack and which is envied, coveted, lusted after. Crime flashes a million brilliant knife blades every minute of the day, and in the night too when waking gives way to dream. Crime is such a tough, such an immense tarpaulin, stretching from infinity to infinity. Where are the monsters who know not crime? What realms do they inhabit? What prevents them from snuffing out the universe?

– Henry Miller, ‘The Air-Conditioned Nightmare’ (New Directions, NY, 1945) pp 86-87

Great Noir Posters: Deadline at Dawn (1946)

Summary Noir Reviews: Between Wall Street and a High Wall

Side Street (1950)

Young postal-worker with no prospects and a pregnant wife makes the mistake of stealing from a crooked lawyer. A tight and savvy noir from Anthony Mann and DP Joseph Ruttenberg explores the claustrophobic canyons of New York and ends with an ironically appropriate ‘crash’ on Wall Street. While the noir atmospherics are there, Sydney Boehm’s screenplay lacks tension, and the leads, Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell, fresh from Nicholas Ray’s They Live By Night (1949), fail to impress. Bravura camera-work and editing in the climactic car chase make the ending exciting, and the signature Mann violence is particularly callous. James Craig as a savage hood is arresting.

Mystery Street (1950)

An innocent everyman takes flight after he is implicated in the brutal murder of a b-girl. A noirish police procedural set in Boston is ok only with disappointing work from DP John Alton. John Sturges directed. The inimitable Elsa Lanchester is great as a conniving landlady, and Jan Sterling is nicely camp as the b-girl, but she is knocked-off early. Bruce Bennett as a Harvard forensic scientist is even more wooden than when he played Mildred Pierce’s boring husband! Rocardo Montalban as the investigating cop is charming but without depth. The denouement is flat as stale beer.

High Wall (1946)

A war vet with a brain tumor that causes blackouts and amnesia is charged with his wife’s murder. A film noir where cars are integral to the story and to the noir aesthetics: fast cars screeching to nowhere, dark streets, rain on asphalt, roadblocks, escape, entrapment… ‘crashing out’. Directer Curtis Bernhardt and his DP Paul Vogel in the many scenes with cars in this picture have fashioned indelibly mystic images of the noir car. An inverted mis-en-scene that contrasts the order and brightness of a mental hospital with the dark and menace of city streets and apartments at night, delivers an interesting dynamic, but the grittiness factor is almost absent. Leads Robert Taylor and Audrey Totter are not up to standard, but Herbert Marshall as the bad guy is palpably rotten.