The Origins of Film Noir: A crash course in film noir its origins and influences

Written with the assistance of learningstudioai.com

The Origins of Film Noir

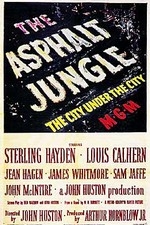

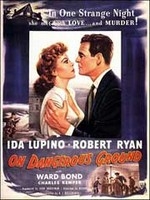

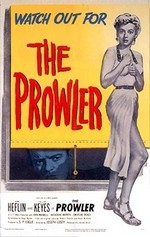

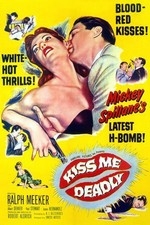

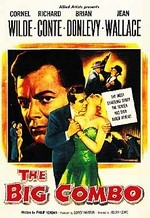

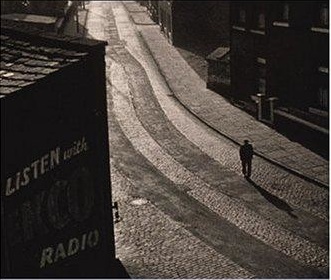

Film Noir a series of atmospheric crime films that emerged in the United States during the 1940s and 1950s, has its roots in several different sources.

Literary Sources

The term “noir” derives from the French word for “black,” which is fitting given the bleak and pessimistic worldview that characterizes many films noir. A primary literary source of Film Noir is hardboiled detective fiction, which developed in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler created tough, cynical detectives who operated in a corrupt and violent world. These stories often featured femme fatales, dangerous women who used their sexuality to manipulate men and often proved to be more deadly than any male villain.

Another important literary influence on Film Noir was the German Expressionist movement, which emerged in Germany during the 1910s and 1920s. Expressionist filmmakers such as Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau used exaggerated sets, dramatic lighting, and distorted camera angles to create a sense of dread and unease. This style was brought to Hollywood by European emigrés fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s, and elements of Expressionism can be seen in many Film Noir classics.

Social and Historical Context

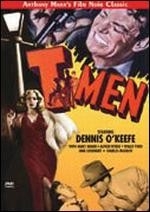

The emergence of Film Noir in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s can be traced to a number of social and historical factors. The post-World War II era was marked by a sense of disillusionment and anxiety, as Americans struggled to come to terms with the horrors of the war and the threat of atomic annihilation. In addition, the period was characterized by a crackdown on organized crime, as law enforcement agencies sought to dismantle the powerful syndicates that had emerged during Prohibition.

This climate of fear and uncertainty is reflected in many films noir. Characters are often haunted by their pasts, struggling to make sense of a world that seems to have lost its moral compass. Crime and violence are pervasive, and justice is often elusive. Many films also explore themes of masculinity and femininity, with male characters struggling to assert their authority in a society that was rapidly changing, and female characters using their sexuality as a means of survival in a patriarchal world.

Cinematic Techniques

Film Noir is characterized by a distinctive visual style that combines elements of Expressionism with innovative cinematic techniques. Low-key lighting, chiaroscuro effects, and deep shadows create a sense of ambiguity and unease, while unusual camera angles and compositions heighten the sense of disorientation. The use of voiceover narration, non-linear storytelling, and flashbacks also contribute to the sense of complexity and ambiguity that is characteristic of films noir.

Overall, the origins of Film Noir are complex and multifaceted, reflecting a convergence of literary, social, and historical factors.

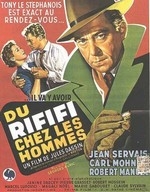

Visual Style and Tropes of Film Noir

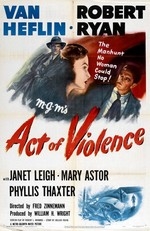

Film Noir is known for its distinctive visual style, which combines moody lighting, shadowy compositions, and unusual camera angles to create an atmosphere of mystery, suspense, and moral ambiguity.

Lighting and Composition

One of the defining features of Film Noir is its use of chiaroscuro lighting, which emphasizes contrasts between light and dark, creating deep shadows and a sense of ambiguity. Low-key lighting is often employed to create dramatic tension, with characters frequently shrouded in darkness or half-hidden in shadow. Unusual camera angles and compositions are also used to heighten the sense of disorientation and uncertainty, with tilted or skewed shots creating a sense of instability and imbalance.

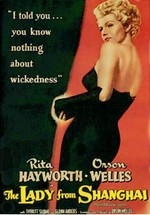

Tropes and Motifs

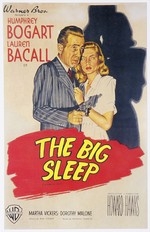

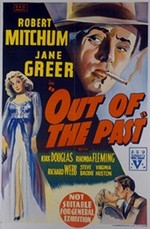

Film Noir is characterized by a number of recurring themes and motifs, many of which draw on the literary sources that influenced the genre. Femme fatales, dangerous women who use their sexuality to manipulate men, are a staple of Film Noir, with characters such as Phyllis Dietrichson in “Double Indemnity” and Kathie Moffat in “Out of the Past” becoming iconic figures. Male protagonists are often flawed or morally compromised, struggling to assert their authority in a corrupt and violent world. The criminal underworld is a frequent setting, with organized crime syndicates often serving as a metaphor for a society that has lost its moral bearings.

Influence and Legacy

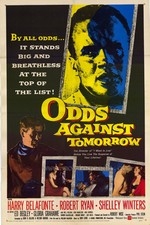

The influence of Film Noir can be seen in a wide range of contemporary films and television shows, with the visual style and thematic concerns of the genre continuing to resonate with audiences today. The emergence of “neo-noir” in the 1970s and 1980s, which updated the genre for a new generation of film-goers.

Gender and Power in Film Noir

Film Noir is often seen grappling with issues of power, corruption, and violence. This module will explore the ways in which these themes intersect with questions of gender and sexuality, particularly with regard to the representation of women in Film Noir.

Femme Fatales

One of the most iconic figures of Film Noir is the femme fatale, a seductive and dangerous woman who uses her sexuality to manipulate men. The femme fatale is often portrayed as a figure of temptation and betrayal, luring male protagonists into a web of deceit and violence. However, some feminist critics have argued that the femme fatale can also be seen as a subversive figure, challenging traditional gender roles and power dynamics by asserting her own agency and independence.

Dangerous Women

In addition to the femme fatale, many films noir feature other dangerous women, such as prostitutes, gangsters’ molls, and other marginalized or criminalized figures. These characters are often depicted as victims of male oppression and exploitation, struggling to assert their own agency and autonomy in a patriarchal world. However, their narratives are often overshadowed by the stories of male protagonists, who are typically presented as more heroic or sympathetic.

Masculinity and Power

The representation of masculinity in Film Noir is also a key theme, with male protagonists often struggling to assert their authority and power in a corrupt and violent world. Some scholars have argued that the genre reflects anxieties about changing gender roles in post-World War II America, with male characters grappling with feelings of emasculation and uncertainty in the face of social and cultural change.

Influences on Film Noir

Poetic realism and German Expressionism were two major film movements that emerged in Europe during the 1920s and 1930s. These movements had a significant impact on the development of film noir in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s.

Poetic realism was a French film movement that emphasized a poetic and melancholic portrayal of working-class life. This movement often focused on themes of love, death, and the struggle for survival. The use of chiaroscuro lighting, deep shadows, and a focus on urban landscapes were key elements of poetic realism.

German Expressionism, on the other hand, was a German film movement that emphasized the subjective experience of the individual. This movement often used distorted sets, exaggerated lighting, and stylized acting to create a sense of psychological tension and unease. German Expressionist films often explored themes of madness, paranoia, and social decay.

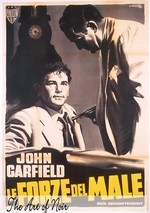

Film noir borrowed heavily from both poetic realism and German Expressionism. Like poetic realism, film noir often portrayed working-class characters struggling to survive in a harsh urban environment. The use of chiaroscuro lighting and deep shadows to create a moody and atmospheric look was also a key element of film noir.

Similarly, film noir borrowed many stylistic elements from German Expressionism. The use of distorted camera angles and stylized lighting to create a sense of psychological tension and unease was a hallmark of many film noir productions. The use of voiceover narration and flashbacks to explore the subjective experience of the protagonist was also a key element of many film noir films.

In summary, poetic realism and German Expressionism were two major film movements that had a significant influence on the development of film noir. The use of chiaroscuro lighting, deep shadows, and a focus on urban landscapes were key elements borrowed from poetic realism, while the use of distorted camera angles, stylized lighting, and exploration of the subjective experience of the protagonist were key elements borrowed from German Expressionism.

Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction: Explore the gritty and suspenseful world of hard-boiled detective fiction

Overview

An introduction to hard-boiled detective fiction, examining its origins, development and legacy, exploring its characteristics, including its gritty portrayal of crime, corruption and violence, and its emphasis on tough, morally ambiguous protagonists who operate in a bleak and unforgiving urban landscape.

Origins and Evolution

Crime Fiction before Hard-Boiled

Before we can understand the origins of hard-boiled detective fiction, we need to look at the earlier forms of crime fiction that preceded it. In the 19th century, crime fiction was dominated by the “whodunit” or classic detective story, which focused on an intellectual sleuth who used logic and deduction to solve a puzzle-like mystery. Famous examples of this style include Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories and Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot novels. However, by the early 20th century, readers were growing tired of the formulaic nature of the whodunit.

Emergence of Hard-Boiled Fiction

In the 1920s and 1930s, a new type of crime fiction emerged that would come to be known as hard-boiled detective fiction. The term “hard-boiled” originally referred to the tough, unsentimental style of writing that characterized this genre, but it has since come to describe the gritty, realistic portrayal of crime, violence and corruption that is its hallmark. Hard-boiled fiction was set apart from earlier crime fiction by its emphasis on the seedy underbelly of society, its complex and ambiguous characters, and its focus on action and suspense rather than puzzle-solving.

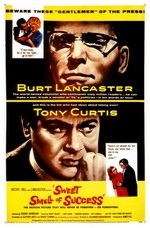

Key Authors and Texts

Some of the key authors and texts that shaped the development of hard-boiled detective fiction include Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain. Hammett’s novel The Maltese Falcon (1930), featuring the iconic private detective Sam Spade, is widely regarded as one of the defining works of the genre. Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels, including The Big Sleep (1939), helped to establish many of the conventions of hard-boiled fiction and are celebrated for their vivid descriptions of 1940s Los Angeles. James M. Cain’s novels such as The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) and Double Indemnity (1943) often focus on the dark passions and desires that drive ordinary people to commit crimes.

Impact and Legacy

Hard-boiled detective fiction has had a lasting impact on popular culture, influencing everything from film noir to contemporary crime films and television dramas, through the genre’s gritty, realistic portrayal of crime and violence, its tough and cynical heroes, and its emphasis on action and suspense. While the genre has evolved and diversified over time, with writers experimenting with different settings, styles and themes, the legacy of hard-boiled detective fiction can still be seen today in works as diverse as Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins novels and Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl.

The Hard-Boiled Protagonist

Characteristics of the Hard-Boiled Protagonist

The hard-boiled protagonist is a central figure in hard-boiled detective fiction. These characters are typically tough, independent, and morally ambiguous. They operate outside of mainstream society, often as private investigators or cops who operate at the margins of the law. They have a tendency to use violence as a means to achieve their goals. They are often hard-drinking, chain-smoking, and cynical about human nature. Many of them are haunted by past traumas, which contribute to their sense of emotional detachment from the world around them.

The Role of the Hard-Boiled Protagonist

The hard-boiled protagonist serves as the narrator and protagonist of many hard-boiled detective stories. Their point of view provides insight into the seedy underworlds they inhabit, and their tough exterior allows them to navigate these underworlds. While they may not always play by the rules, they are driven by a sense of justice and a desire to protect the innocent. The hard-boiled protagonist often finds themselves caught up in complex webs of corruption, betrayal, and violence, and must rely on their wits and their fists to survive.

Evolution of the Hard-Boiled Protagonist

Over time, the character of the hard-boiled protagonist has evolved, reflecting changes in society and culture. In the early days of the genre, hard-boiled heroes were almost exclusively white, male, and heterosexual. However, as the genre developed, writers began to experiment with different types of heroes. The African American detective Easy Rawlins, created by Walter Mosley in the 1990s, is one example of a hard-boiled protagonist who breaks the mould. Rawlins operates in a predominantly African American neighbourhood in Los Angeles and faces racism and oppression on a daily basis. His experiences as a black man in America shape his perspective and his approach to solving crimes.

The Legacy of the Hard-Boiled Protagonist

The legacy of the hard-boiled protagonist can be seen in popular culture today. Characters like James Bond, Jason Bourne, and John McClane all share some characteristics with the hard-boiled hero, such as their toughness, their independence, and their willingness to use violence to achieve their goals. However, the genre has also inspired writers to create more complex and diverse protagonists, reflecting changes in our understanding of society and human nature. The legacy of the hard-boiled protagonist continues to evolve, inspiring new generations of writers and readers to explore the darker side of crime and justice.

Gender and Representation

Women in Hard-Boiled Fiction

Women have traditionally been marginalized in hard-boiled detective fiction, often appearing as femme fatales or victims of male violence. These characters are typically defined by their sexuality rather than their agency, serving as plot devices to drive the narrative forward. However, there are some notable exceptions to this trend. For example, in Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely, the character of Velma is a complex and nuanced portrayal of a strong female character who challenges gender norms. Similarly, authors like Sara Paretsky and Sue Grafton have created female detectives who operate within the hard-boiled tradition, such as V.I. Warshawski and Kinsey Millhone.

LGBTQ+ Representation

LGBTQ+ characters have also been historically underrepresented in hard-boiled detective fiction. However, in recent years, there has been a push towards increased representation and diversity in the genre. Writers like Joseph Hansen and Michael Nava have created LGBTQ+ detectives who confront issues of homophobia and discrimination in their work. Additionally, some contemporary writers have worked to subvert traditional gender roles by creating LGBTQ+ characters who challenge expectations and stereotypes.

Challenging Traditional Gender Roles

Many writers have used hard-boiled detective fiction as a means of challenging traditional gender roles. For example, in her novel Indemnity Only, Sara Paretsky created a female private investigator who defies gender norms through her tough exterior and willingness to use violence. Similarly, James Ellroy’s novel The Black Dahlia features a female character who is unapologetically sexual and independent, challenging the gender roles of the era in which the story is set.

Impact and Legacy

The representation of gender and sexuality in hard-boiled detective fiction has evolved significantly over time. While the genre has traditionally been dominated by male protagonists and marginalizing portrayals of women, LGBTQ+ characters, and people of colour, there have been notable efforts to challenge these stereotypes and increase diversity within the genre. The legacy of hard-boiled detective fiction continues to be felt today, inspiring writers to explore new perspectives on gender and representation in their work.

German Expressionism

German Expressionism, an influential art movement that emerged in Germany during the early 20th century. The social, cultural, and political climate that gave rise to the movement reflected the anxieties and tensions of the period.

Origins and Characteristics

German Expressionism is an art movement that emerged in Germany during the early 20th century. It is characterized by its bold colours, distorted forms, and exaggerated emotions, which reflected the anxieties and tensions of its time.

Historical Context

German Expressionism emerged during a tumultuous period in German history. The country was grappling with social, cultural, and political upheavals, including industrialization, urbanization, and rapid technological advances. At the same time, World War I had a profound impact on German society, causing widespread trauma and disillusionment. These changes created a sense of dislocation and fragmentation, which artists sought to capture in their work.

Key Figures

Several key figures played a significant role in shaping German Expressionism. One of the most important was Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who founded the group Die Brücke (The Bridge) in 1905. Kirchner’s work was characterized by its vivid colours, angular lines, and distorted forms, which conveyed a sense of emotional intensity. Other important members of Die Brücke included Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Max Pechstein.

Another influential group was Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), founded by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc in 1911. This group emphasized spirituality and mysticism in their work, often using abstract forms and vibrant colours to convey spiritual experiences. Other key members of Der Blaue Reiter included August Macke and Paul Klee.

Defining Features

German Expressionism is characterized by several defining features, including:

- Emotional intensity: Expressionist artists sought to convey intense emotions, often through bold colours, exaggerated forms, and distorted perspectives.

- Social commentary: Many Expressionist works were intended as social commentary, critiquing the political and cultural norms.

- Primitivism: Expressionist artists often drew inspiration from non-Western art forms and cultures, seeking to create a more authentic and primal form of expression.

- Subjectivity: Expressionist art is highly subjective, emphasizing the inner experiences and emotions of the artist over objective reality.

Conclusion – Origins and Characteristics

German Expressionism was a ground-breaking art movement that had a profound impact on modern art. Its bold colours, distorted forms, and exaggerated emotions captured the anxieties and tensions of its time, while its emphasis on subjectivity and emotional intensity paved the way for later movements such as Abstract Expressionism.

Themes and Motifs

German Expressionism was a highly diverse art movement, encompassing a wide range of styles, subjects, and themes. However, there are several recurring motifs and themes that appear in many Expressionist works, including social criticism, alienation, and the city.

Social Critique

One of the most important themes in German Expressionism was social criticism. Expressionist artists sought to critique the political and cultural norms of their time, often by exposing the injustices and inequalities of modern society. For example, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s painting “Street, Berlin” depicts a chaotic and fragmented urban scene, with isolated individuals struggling to find their place in the crowded city. This work can be seen as a commentary on the dehumanizing effects of modern urban life.

Alienation

Another recurring theme in German Expressionism was alienation. Many Expressionist works explored the sense of isolation and dislocation experienced by individuals in modern society. For example, Edward Munch’s painting “The Scream” depicts a figure screaming in anguish against a blood-red sky. This work can be seen as a powerful expression of existential dread and alienation.

The City

The city was another important motif in German Expressionist art. Expressionist artists often depicted urban scenes as chaotic, fragmented, and oppressive. This reflected their critique of modern urban life, which they saw as dehumanizing and alienating. For example, George Grosz’s painting “Metropolis” depicts a crowded and claustrophobic cityscape, with anonymous figures jostling for space and struggling to maintain their individuality in the face of overwhelming social forces.

Primitivism

Primitivism was another important influence on German Expressionism. Expressionist artists looked to non-Western art forms and cultures for inspiration, seeking to create a more authentic and primal form of expression. For example, Emil Nolde’s painting “Dance Around the Golden Calf” draws on the biblical story of the Israelites worshipping a golden calf, but reimagines it as a pagan celebration with masks and wild dancing. This work can be seen as a rejection of traditional Christian morality and a celebration of primal impulses.

Conclusion – Themes and Motifs

German Expressionism was a highly diverse art movement that explored a wide range of themes and motifs. However, social critique, alienation, the city, and primitivism were all recurring themes that appeared in many Expressionist works.

Legacy and Influence

German Expressionism may have been a short-lived art movement, but its impact on modern art was profound and enduring. The legacy and influence of German Expressionism, including its impact on later art movements, its significance in film and theatre, and its role in shaping modern German identity.

Impact on Later Art Movements

German Expressionism had a significant impact on later art movements, particularly Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism. Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were inspired by Expressionism’s emphasis on subjective emotion and gesture, while Neo-Expressionists like Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer drew on Expressionism’s interest in symbolism and mythology. The influence of German Expressionism can also be seen in the work of later artists like Francis Bacon and David Hockney.

Film and Theatre

German Expressionism had a significant impact on film and theatre, particularly in the horror and science fiction genres. Films like F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” and Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” drew on Expressionism’s use of light and shadow, exaggerated perspectives, and distorted forms to create haunting and surreal imagery. Expressionist theatre, meanwhile, emphasized the use of masks, stylized movement, and symbolic storytelling. This influence can be seen in the work of later filmmakers like Tim Burton and Guillermo del Toro.

Modern German Identity

German Expressionism played an important role in shaping modern German identity, particularly after World War II. In the aftermath of the war, many Germans sought to distance themselves from the atrocities of the Nazi regime and reclaim their cultural heritage. German Expressionism provided a way to do that, emphasizing the humanistic and spiritual values of German culture rather than its militaristic past. This shift in perspective can be seen in the work of post-war artists like Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter, who drew on Expressionist themes and imagery to create a new, more humanistic form of German art.

Legacy and Influence

German Expressionism may have been a short-lived art movement, but its impact on modern art, film, and theatre was profound and enduring. Its influence can be seen in later art movements like Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism, as well as in the work of filmmakers and theatre directors. Perhaps most importantly, German Expressionism played a key role in shaping modern German identity, providing a way for Germans to reclaim their cultural heritage and move beyond the trauma of World War II.

Poetic Realism in Film: Explore the aesthetic and thematic elements of poetic realism in cinema

Overview

Poetic Realism was a film movement that emerged in France during the 1930s. Identifiable aesthetic and thematic elements define this genre, including its use of atmospheric settings, complex characters, and social commentary, influencing later movements in world cinema.

Origins and Characteristics

The poetic realism movement in cinema emerged in France during the 1930s in response to the political and social upheaval of the time. The movement was characterized by a focus on the emotional and psychological experiences of characters, as well as an emphasis on atmospheric settings and naturalistic acting.

Historical Context

The origins of poetic realism can be traced back to the aftermath of World War I, which had a profound impact on French society. The devastation of the war led to a sense of disillusionment and a questioning of traditional values and institutions. This sense of disillusionment was compounded by the Great Depression, which hit France particularly hard in the early 1930s.

Against this backdrop, a group of filmmakers began to explore new ways of representing reality on screen. They rejected the glossy, escapist films that were popular at the time in favour of a more gritty and realistic style. These filmmakers believed that cinema had the power to reflect and critique society, and they sought to use the medium to address pressing social and political issues.

Characteristics of Poetic Realism

At its core, poetic realism is a style that prioritizes mood and atmosphere over plot. The films of the movement often feature brooding, shadowy landscapes and complex, flawed characters who are struggling to come to terms with their place in the world. The dialogue is sparse and understated, and the camera work emphasizes the beauty and mystery of the natural world.

One of the key features of poetic realism is its use of non-professional actors. Filmmakers would often cast local residents or amateurs in small roles, adding a sense of authenticity to the performances. This approach also allowed for greater flexibility in terms of shooting locations and schedules.

Another hallmark of poetic realism is its exploration of existential themes such as alienation, despair, and the search for meaning. The films often depict characters who are caught between two worlds – the urban and the rural, the past and the present, the individual and the collective. These characters are struggling to find their place in a society that is rapidly changing and often hostile.

Key Films of Poetic Realism

Notable films of the poetic realism movement include Jean Renoir’s “La Grande Illusion” (1937), Marcel Carné’s “Le Quai des Brumes” (1938), and Julien Duvivier’s “Pepe le Moko” (1937). These films are characterized by their lyrical, dreamlike quality and their focus on the lives of ordinary people.

“La Grande Illusion”, tells the story of a group of French soldiers who are taken prisoner during World War I. The film explores the themes of class, nationality, and social hierarchy, and it critiques the futility of war. Similarly, “Le Quai des Brumes” follows the story of a disillusioned soldier who falls in love with a young woman in a port town. The film is noted for its atmospheric cinematography and its depiction of a world filled with desperation and longing.

Conclusion – Origins and Characteristics

The origins and characteristics of poetic realism in cinema are closely tied to the historical and cultural context in which the movement emerged. Although it only lasted for a few years, poetic realism had a significant impact on the development of world cinema, influencing subsequent movements such as Italian neorealism and the French New Wave.

Key Films and Filmmakers

The poetic realism movement in cinema produced a number of notable films and filmmakers during its brief existence. While many of these films are now considered classics of world cinema, they were often controversial and divisive at the time of their release.

Jean Renoir

Jean Renoir is widely regarded as one of the key figures of the poetic realism movement. His film “La Grande Illusion” (1937) is often cited as one of the most important films of the genre. The film tells the story of a group of French soldiers who are taken prisoner during World War I and features a cast that includes Jean Gabin and Erich von Stroheim.

Renoir’s other notable work from this period includes “Boudu Saved from Drowning” (1932), a comedy about a vagrant who is rescued from drowning by a bourgeois Parisian family, and “The Crime of Monsieur Lange” (1936), a satirical look at the French publishing industry.

Marcel Carné

Marcel Carné is another prominent filmmaker associated with poetic realism. His film “Le Quai des Brumes” (1938) is often cited as one of the defining works of the genre. The film tells the story of a disillusioned soldier who falls in love with a young woman in a port town and features iconic performances from Jean Gabin and Michèle Morgan.

Carné’s other notable films from this period include “Jenny” (1936), a drama about a woman who turns to prostitution after losing her job, and “Le Jour se Lève” (1939), a tragic love story set against the backdrop of a working-class neighbourhood.

Julien Duvivier

Julien Duvivier is perhaps best known for his film “Pepe le Moko” (1937), which stars Jean Gabin as a notorious thief hiding out in the Casbah of Algiers. The film is noted for its atmospheric cinematography and its depiction of a world filled with danger and intrigue.

Duvivier’s other notable films from this period include “La Bandera” (1935), a drama about a disillusioned soldier who becomes involved with a group of criminals, and “Un Carnet de Bal” (1937), a nostalgic look at the lives of several women who attend a ball together.

Other Notable Films

In addition to the works of Renoir, Carné, and Duvivier, there were a number of other notable films produced during the poetic realism era. These include:

- “Le Quai des Brumes” (1938) directed by Marcel Carné, which tells the story of a deserter who finds refuge in a port town and falls in love with a young woman.

- “Le Jour se Lève” (1939) directed by Marcel Carné, which follows the story of a working-class man who becomes embroiled in a love triangle.

- “Quai des Orfèvres” (1947) directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, which combines elements of poetic realism with film noir to tell the story of a murder investigation in Paris.

Conclusion – Key Films and Filmmakers

The films produced during the poetic realism movement continue to captivate audiences today, thanks in part to their emphasis on mood and atmosphere over plot. While many of these films were controversial and divisive at the time of their release, they have since been recognized as important works of world cinema. The filmmakers associated with poetic realism, including Jean Renoir, Marcel Carné, and Julien Duvivier, helped to shape the medium of cinema and set the stage for future generations of filmmakers.

Legacy and Influence

Although the poetic realism movement in cinema was relatively short-lived, lasting from roughly 1934 to 1940, the movement had a significant impact on the development of world cinema, shaping subsequent movements such as Italian neorealism and the French New Wave.

Italian Neorealism

Italian neorealism emerged in the wake of World War II, and like poetic realism, it was characterized by a focus on social issues and a rejection of traditional Hollywood-style storytelling. Films in this movement often featured non-professional actors and were shot on location in urban and rural settings.

One of the key figures associated with Italian neorealism, Roberto Rossellini, cited Jean Renoir’s “Toni” (1935) as a major influence on his work. Similarly, Vittorio De Sica, another prominent figure of Italian neorealism, credited Marcel Carné’s “Le Quai des Brumes” (1938) as a formative influence on his filmmaking style.

The French New Wave

The French New Wave, which emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s, was heavily influenced by the poetic realism movement. Filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, sought to break free from traditional cinematic conventions and explore new forms of storytelling.

One of the key features of the French New Wave was its emphasis on mood and atmosphere over plot, a hallmark of the poetic realism movement. The films of the French New Wave often featured complex, flawed characters who were struggling to find their place in a rapidly changing society.

Contemporary Cinema

The legacy of the poetic realism movement can also be seen in contemporary cinema.

An example of this influence can be seen in the work of director Terrence Malick, whose films often feature lush, atmospheric landscapes and a focus on the inner lives of his characters. Similarly, the work of directors such as Wong Kar-wai and Pedro Almodóvar has been compared to the poetic realism movement due to their emphasis on mood and emotion.

Conclusion – Legacy and Influence

The legacy of the poetic realism movement in cinema is far-reaching, extending well beyond its brief existence in the 1930s with the movement’s emphasis on mood and atmosphere over plot, shaping the development of subsequent movements in world cinema. By rejecting traditional Hollywood-style storytelling and focusing on the emotional and psychological experiences of their characters, the filmmakers associated with poetic realism helped to shape the medium of cinema and set the stage for future generations of filmmakers.